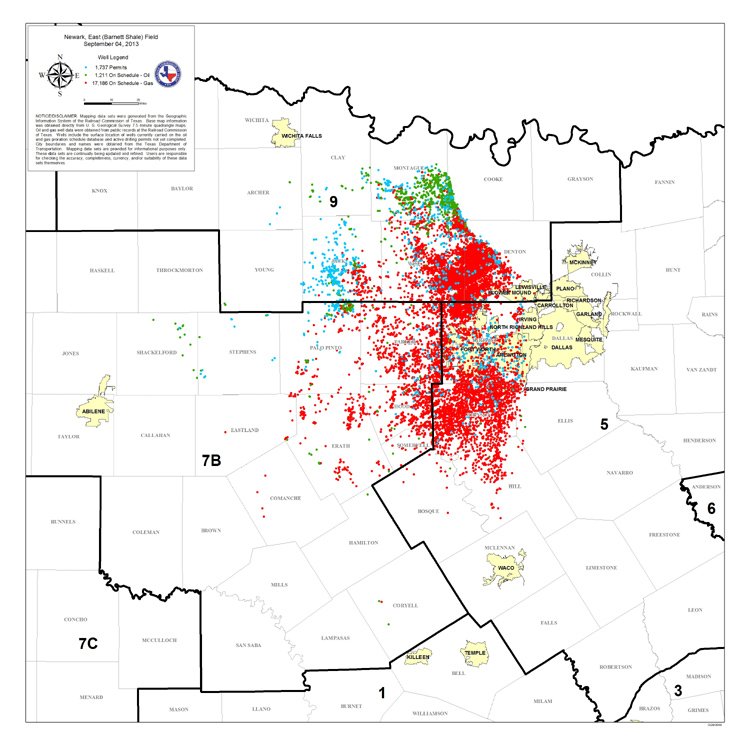

Map of existing permits and wells currently carried on the oil proration schedule and gas proration schedule database.

The American shale gas revolution began in the area that goes under the name of the Barnett Shale. On the map above you can see existing permits and wells. The Railroad Commission of Texas (RRA) is the organization that holds responsibility for the official oil- and gas statistics in Texas. On 22 August 2013, the RRA published the latest statistics on the Barnett Shale (see report). The official name of the area that lies from southwest to northwest of Dallas is not the Barnett Shale but, rather, “The Newark, East Field.” According to the RAA, the area is 13,000 square kilometers in size, and in Sweden, the area of Uppland is a comparable size, 12,676 square kilometers. The fact that Stockholm lies in an outer area of Uppland makes the comparison even better since the Barnett Shale lies partially under Dallas.

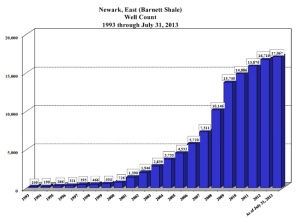

First, let’s look at the total number of wells that have been drilled. In July, that number passed 17,000 (at the end of July it was 17,067 wells). If we divide the area of the Barnett Shale by the number of wells, we obtain a surface area per well of approximately 900 meters x 900 meters (in reality, 875m x 875m). Imagine the whole of Uppland divided up into a patchwork where every square is 900 meters x 900 meters, and in every square, there is a “fracking” well. An international comparison can be Belgium with 30,528 square kilometers, i.e. the Barnett Shale is nearly half the area of Belgium (43%). We see in the figure that the number of new wells per year is decreasing from the peak year in 2009 when 3594 wells were drilled to only 840 new wells in 2012. In the report, “Drill Baby Drill” David Hughes has made a detailed study of the Barnett Shale, and the report includes activities up until May 2012. For individual wells, the production in newly drilled wells falls by 61% in the first year and this fact and the fact that production continues to decline after that means that every year 1507 new wells must be drilled to maintain a constant level of total production. The fact that they drilled 840 new wells in 2012 should mean therefore that production will decline in 2013.

A permit is required for permission to drill a well, and in total there are 24,000 permits currently issued. Of these, 17,000 permits have been used. We see that the greatest number of permits was issued in 2008 when the price of oil and gas rose sharply and the decrease in 2009 would, therefore, seem natural. That new permits have fallen to a level less than the critical number of new wells required to maintain constant production, 1507 wells, may be a sign that the Barnett Shale has now reached and passed maximal production. The low price of natural gas can also be a reason for the reduced interest in drilling for shale gas. The message for the future of the USA is clear – it will not be flooded by an excess of cheap natural gas.

The production trend that David Hughes called “flat” in 2012 has now been replaced by “declining, ” and the fact that they are not drilling enough new wells will mean that we can expect a continued decrease in production. In 2011 the Barnett Shale contributed 21.6% of total shale gas production, how much will it be in the future? At the University of Texas, Austin they have made a detailed study of the future of natural gas production from the Barnett Shale: “New, Rigorous Assessment of Shale Gas Reserves Forecasts Reliable Supply from Barnett Shale Through 2030“. The decline we see in the production is exactly what they predict would happen.

In the figure above we see an apparently increasing trend in production up to December 2011 that then levels off. Earlier we showed that the Barnett Shale during this time had a constant rate of production. The Haynesville Shale has declined somewhat, and this has been compensated by a small increase in the Marcellus Shale. Regarding future production, we currently see no signs that this will increase markedly. Therefore, it’s hard to understand how the USA’s energy authority, the EIA, can suggest that future shale gas production will double by 2040. It is the figure below that makes many economists dream of a future of unlimited natural gas. The reality is now knocking at the door.

(You can discuss this post on Aleklett’s Energy Mix.)